“I didn’t know that wildlife species are protected even outside their natural habitats,” Bekoka said, acknowledging that the program equipped him with new knowledge and skills to comb at illegal wildlife trafficking. Learning how traffickers change their concealment methods daily motivated him to be more vigilant in his daily searches.

Recently, a team of police officers who participated in the program seized 20 kilograms of pangolin scales and rescued three sitatunga antelopes at Kinshasa markets. They also arrested three traffickers, whose cases are now before the courts. “For our first field operation, it was emotional but rewarding,” said Berthold Ofutanya, the unit commander. “We’re developing the skills needed to make a real impact in fighting wildlife trafficking.”

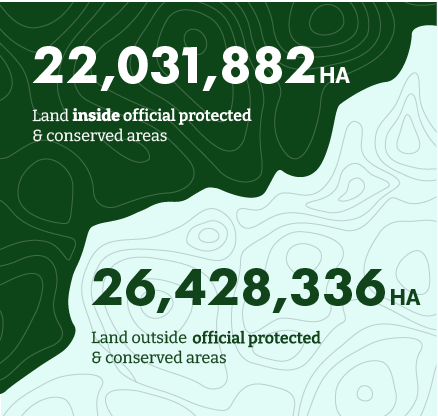

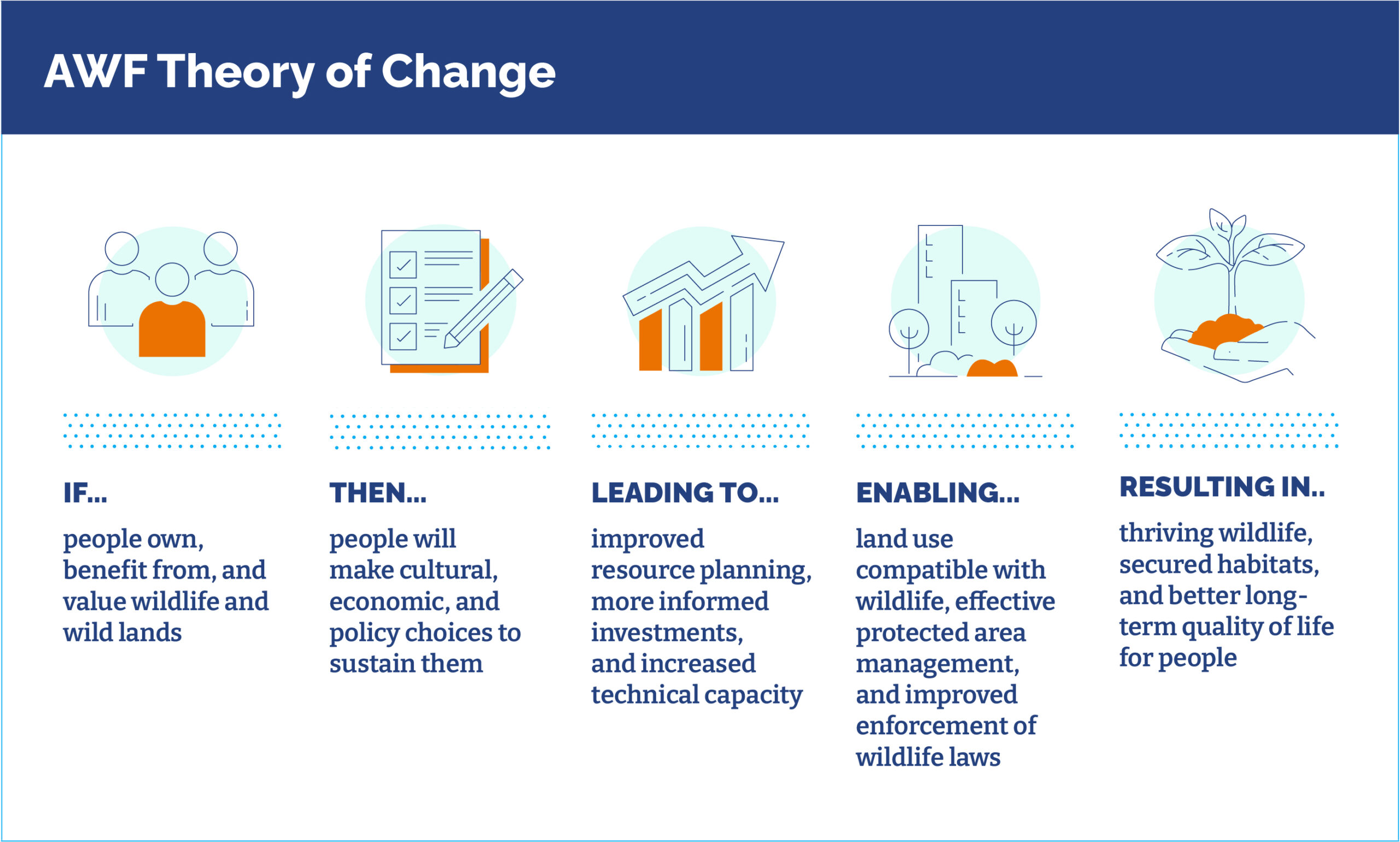

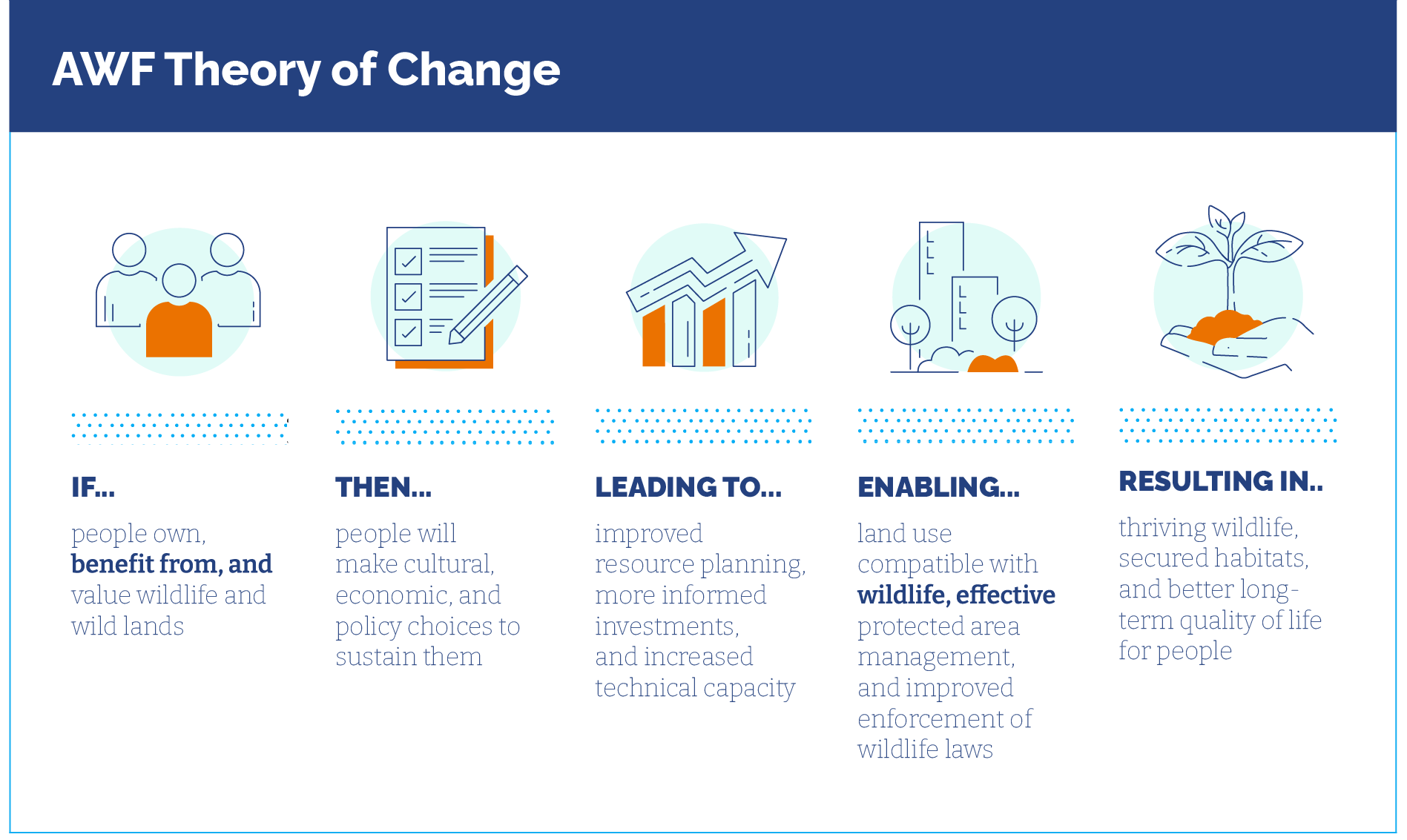

The Wildlife Investigation & Emerging Crimes program is part of a strategically designed set of integrated services, interventions, advocacy, and policy efforts AWF has developed to detect, deter, investigate, and prosecute wildlife crime.

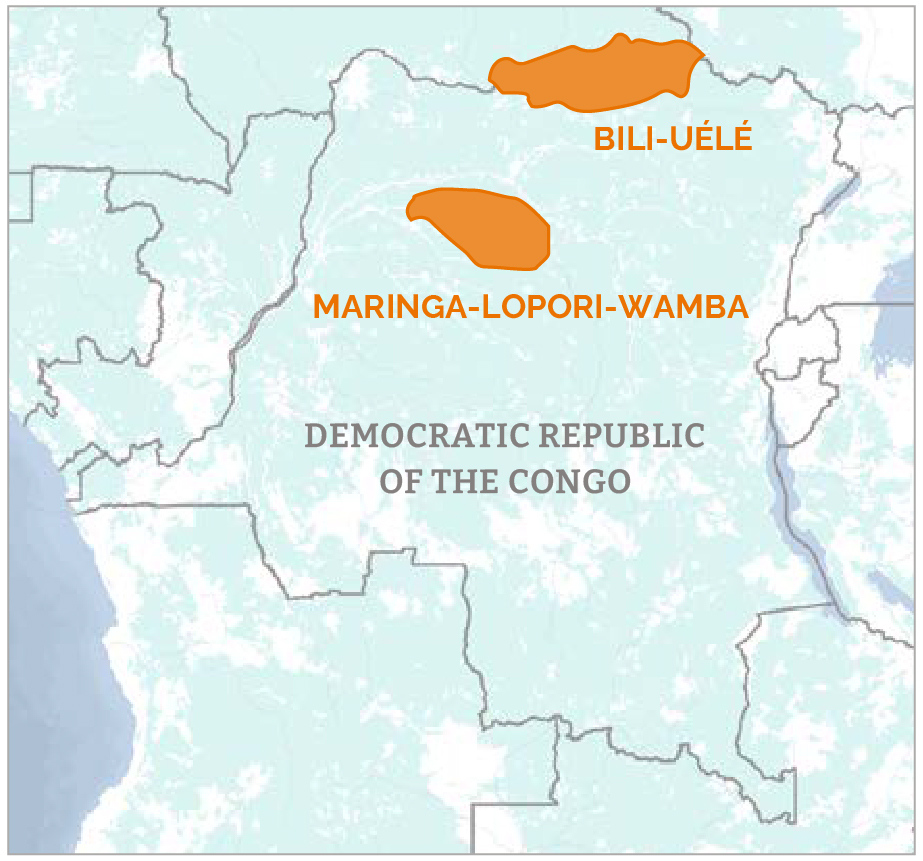

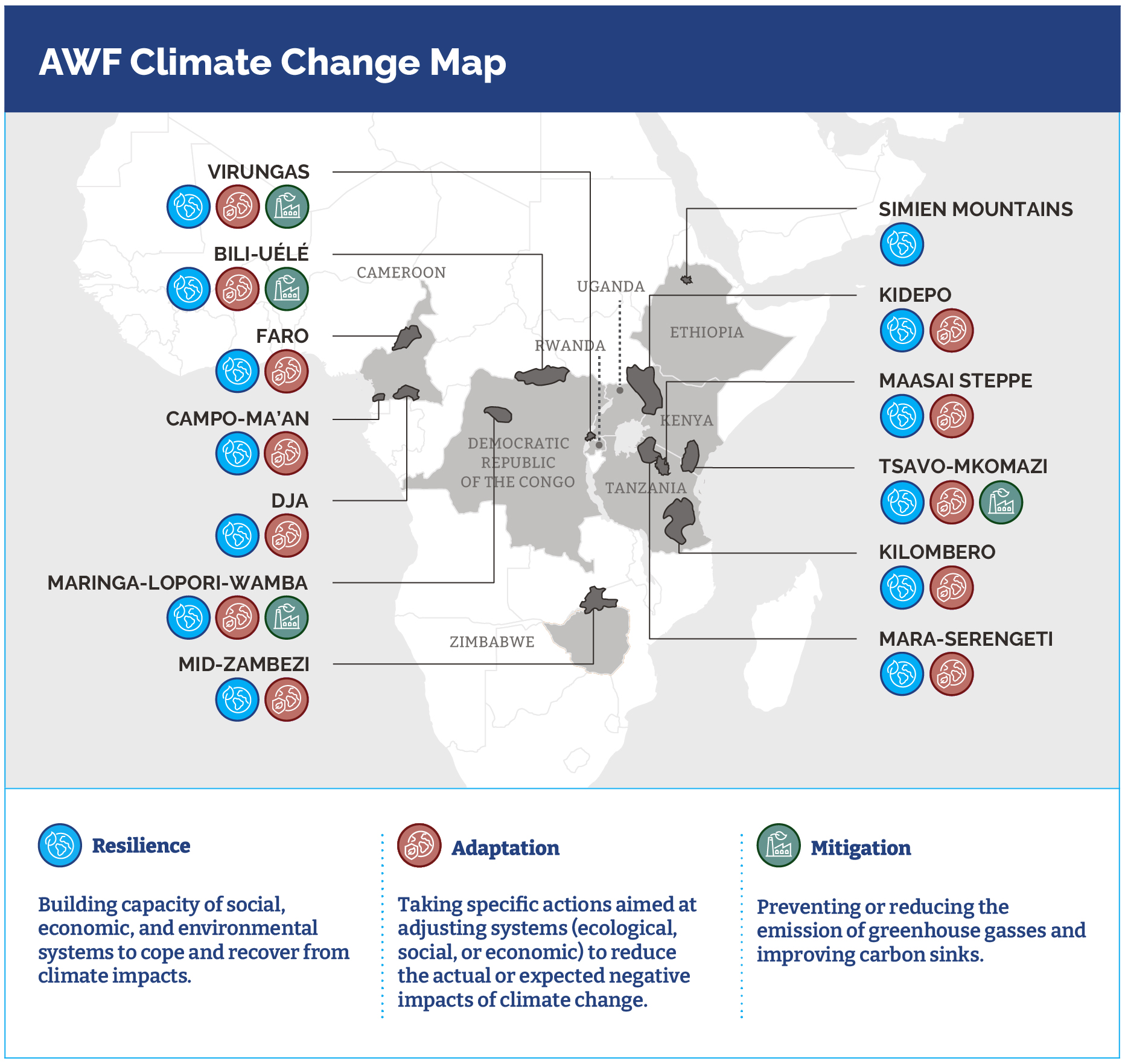

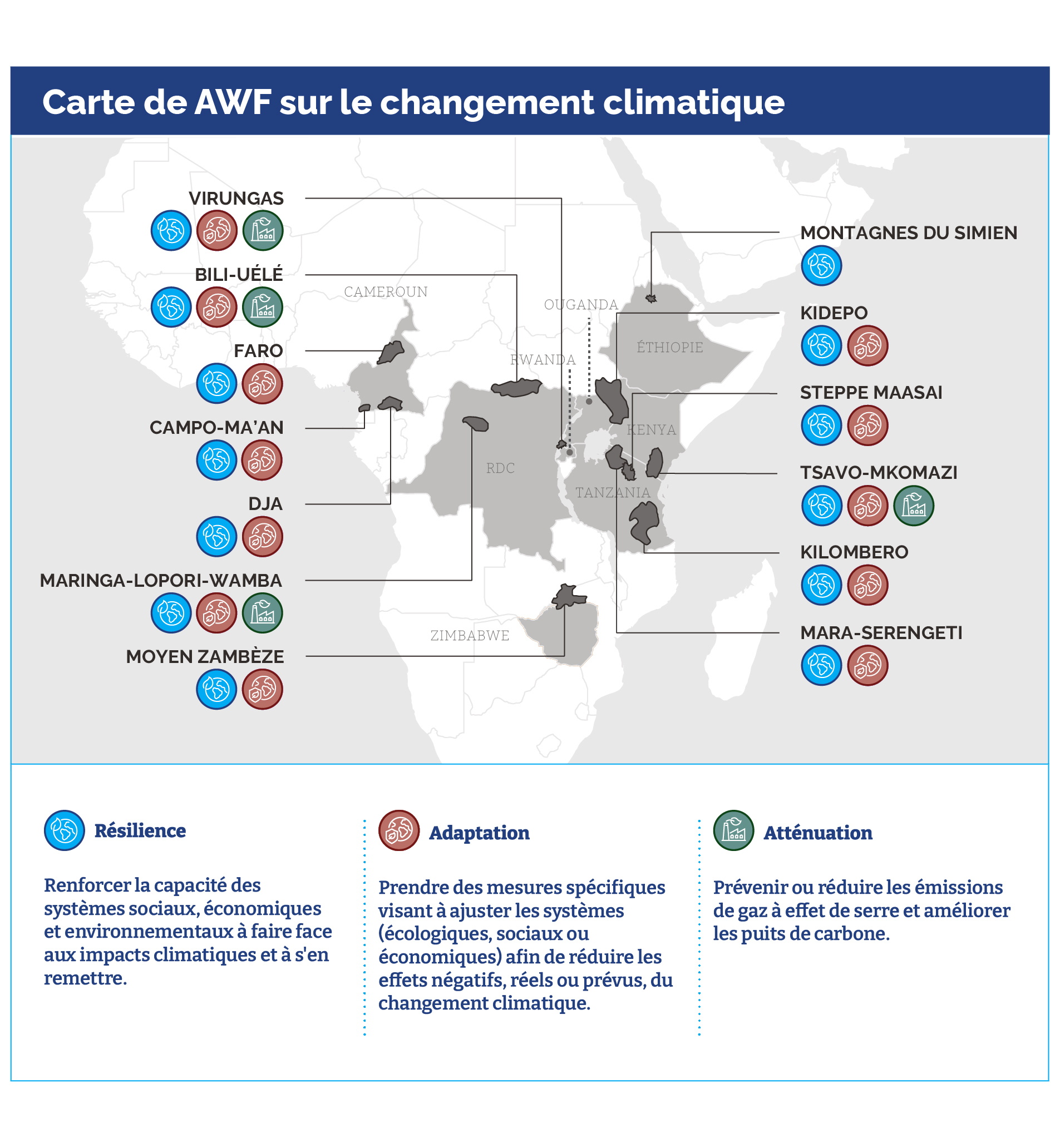

Currently, we are applying our counter wildlife trafficking approach in five countries: the DRC, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. In addition to training programs for law enforcement and the judiciary, we conduct wildlife policy and legislative analyses, provide court monitoring, and train and equip canine detection and deterrence teams.

DRC: THE PUBLIC PROSECUTOR AT THE HIGH COURT OF GOMBE SWEARS IN SEVEN NEW JUDICIAL POLICE OFFICERS WITH THE INSTITUT CONGOLAIS POUR LA CONSERVATION DE LA NATURE, THE DRC’S WILDLIFE AUTHORITY, ON APRIL 27, 2024, IN KINSHASA FOLLOWING THEIR COMPLETION OF AWF’S WILDLIFE JUDICIAL AND PROSECUTORIAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAM. © AWF